Search

Climate

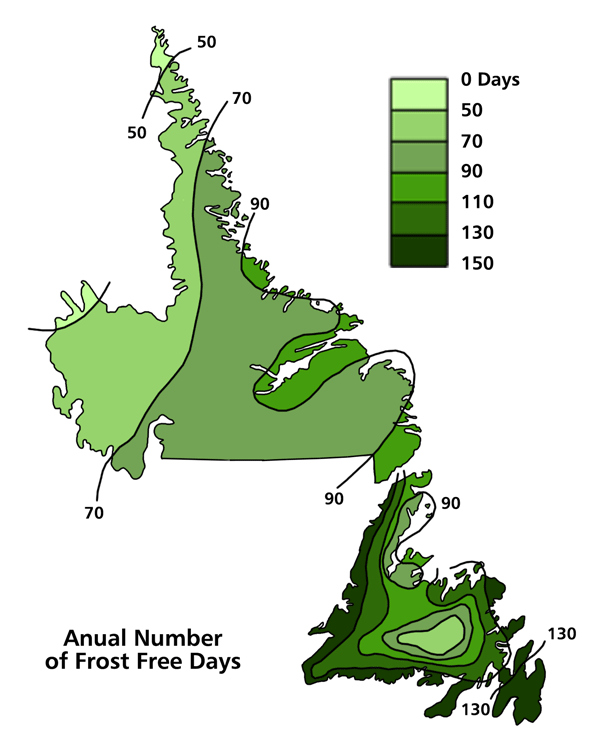

The southeast Avalon is surprisingly temperate. It’s cool in the summer and not too cold in the winter. The mean annual temperature is 5.5C (42F) with mean highs of 11C (52F) in July and -1C (30F) in February. Our south coast area has a mean temperature 5C warmer than St. John’s. The area is one of the warmest areas in winter in Atlantic Canada. It does, however, rain a bit, measuring annually between 1200 mm (236 in.) and 1500mm (295 in.), similar to Vancouver.

Source: http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/environment/images/newfoundland-labrador-frost-free-days.gif

Source: http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/environment/images/newfoundland-labrador-frost-free-days.gif

The climate is strongly influenced by the proximity of the Atlantic Ocean. Our area is dominated by the confluence of the cold Labrador Current that flows down the east coast and the warm Gulf Stream waters flowing up from the southwest. The mixing of the currents produces fog especially in spring and summer when prevailing winds are from the south and southwest. In early summer visitors driving south from Cappahayden will often experience fog as they approach the barrens. An anomaly is the relative absence of fog in Trepassey Harbour. Trepassey’s unique long harbour with its surrounding forested hills and relatively shallow warm waters likely account for the absence of fog.

Large iceberg grounded off the southeast coast

Large iceberg grounded off the southeast coast

In spring and into early summer the occasional iceberg brought down by the Labrador Current will ground along the southeast coast and westward along the southern shore.

Climate Change in the Southeast Avalon

Before we leave this subject we would be remiss if we did not talk about Climate Change. It seems likely that there will be few places on earth that will not be affected. Low-lying areas of Southeast Avalon will certainly be impacted by rising sea levels caused by melting glaciers and the expansive impacts of warmer sea temperatures. We will confine our discussion to some of the impacts that might affect local wildlife.

The Rise in Ocean Temperatures

There is little doubt that surface ocean temperatures off the south coast of Newfoundland have been increasing for a considerable period of time. Swimming in 16-20C waters of Biscay Bay in mid-August would have been unheard of 40 years ago. This is part of a world-wide phenomena connected to climate change. In recent years climate scientists have come to understand that their predictive models did not adequately account for the ocean’s ability to absorb heat.

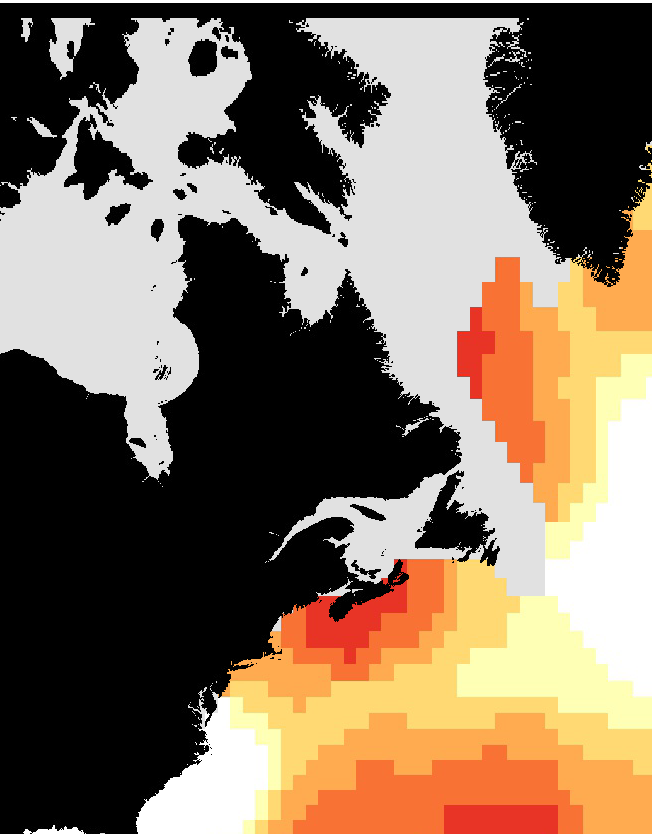

Recent research has determined that across the oceans the pattern of ocean temperature change is quite variable. This is pointed out in a letter by Dan A. Smale et al entitled “Marine Heatwaves threaten global biodiversity and the provision of ecosystem services” date March 4, 2019 in the on-line Journal Nature Climate Change .

Smale’s letter includes evidence that the water temperatures in the global ocean have warmed substantially over the past century. Along with persistent long term warming, discrete periods of extreme regional ocean warming (MHWs) have increased in frequency. A very interesting map below, kindly provided by the author, displays the areas in the north Atlantic where these discrete periods of extreme regional warming have taken place. You will see Atlantic Canada and Newfoundland in the upper left side of the map.

In the mid-North Atlantic there has been effectively no change. The same situation is evident along the east coast of Newfoundland and the Avalon where the Labrador Current flows. On the other hand the waters off Massachusetts, Maine, in the Bay of Fundy, off Nova Scotia and southern Newfoundland show up as an area undergoing the most extreme regional warming trend.

The Gulf Stream

Added to this situation is the flow rate, the temperature at surface and depth, and the location of the Gulf Stream. It is understood that the flow rate is down but this may well be offset by warmer waters in the current as a result of warmer ocean temperatures in the mid-Atlantic. Indeed the historical map of extreme regional ocean warming above also shows large increases in water temperatures off the northeast coast of South America north through the eastern Caribbean and offshore North America all the way to the mid-American States.

If the flow rate in the Gulf Stream is down, but water temperatures in the current are up this phenomena might reduce the circular flow rate of the Labrador Current. If this effect occurs the Gulf Stream may drift north, closer to southeastern Newfoundland. Increased ocean temperatures in the Atlantic are a known fact that have been directly linked to the increased severity of hurricanes affecting the southeastern United States in recent years.

Impact of Warmer Waters on the Wildlife in the southeastern Avalon

While it is not clear how climate change will ultimately affect the climate and wildlife in southern Avalon, there is no doubt that ocean temperatures are rising. This may well be a factor in the movement of some Northern Right Whales away from the mouth of the Bay of Fundy into the Gulf of St. Lawrence and in one known case to southeast Avalon waters. In recent years there have also been sightings of Leatherback Turtles off the south and southeast coast of Newfoundland and more regular sightings of Ocean Sunfish off the Avalon. Both of these tropical species prey on jellyfish which are normally associated with warmer waters.

Climate change impacts that create warmer ocean temperatures will likely affect the variety and populations of some land and seabirds. Certainly in recent years, Cory’s Shearwaters, a Gulf Stream species more regularly found off Nova Scotia, have been recorded in inshore southern Avalon waters for the first time. The recent record of a Brown Booby at Long Beach in summer may be initial evidence of some movement north of tropical seabirds. There is probably not enough time series data on the populations in our seabird colonies to determine any long term changes.

The long-term status of resident and migratory land birds is just as unclear. The breeding populations of Red-breasted Nuthatch, Ruby-crowned Kinglet, Black and White, Mourning, American Redstart and Magnolia Warblers are quite low, and in some years non-existant. In areas as close as Lamanche Provincial Park to the north they are regular breeders. While there may be numerous factors for this difference there is no doubt that historically the southern Avalon has been cooler in summer. If warmer water temperatures raise average summer temperatures and/or reduce the incidence of fog, one might anticipate that at least some of these species might become regular breeders in our area as well. Currently there is no baseline scientific data to measure this. What seems to be evident during our 15+ year summer residence in the south Avalon is that the number of fog days has been slowly reducing. Assuming this does result in slightly warmer summers we might see the evidence of climate change show up in regular and increasing breeding populations of these bird species.

For the naturalist climate change can be a mixed blessing. For those visiting the southeast Avalon for the first time, seeing a Ruby-crowned Kinglet or a Magnolia Warbler here can be understood is a special event, another interesting dimension to the what is already an outstanding natural history area.

For additional information on the climate, vegetation and wildlife of our area the work of Paul Ryan on behalf of the East Coast Trail Association is also recommended. Ryan’s paper provides significant detail on the natural history of the Avalon, much of it applicable to the southeast Avalon (http://www.ucs.mun.ca/~patrickr/TrailTales/).