Search

The People

Old World Meets New

Just over a decade after Columbus “discovered” the New world, Europeans began to visit the southeast Avalon. From about 1505, over one hundred years prior to Champlain’s founding of Quebec in 1608, fishermen arriving in caravels from France, Spain and Portugal occupied Renews and Trepassey from early spring to late fall. They came for the rich stocks of cod on the Grand Banks first reported by John Cabot in 1497. These seasonal residents pursued the salt-cod fishery, which came to dominate the commerce of the southern Avalon and Newfoundland and Labrador for over four centuries before the era of refrigeration.

http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/images/caravel-500.jpg

http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/images/caravel-500.jpg

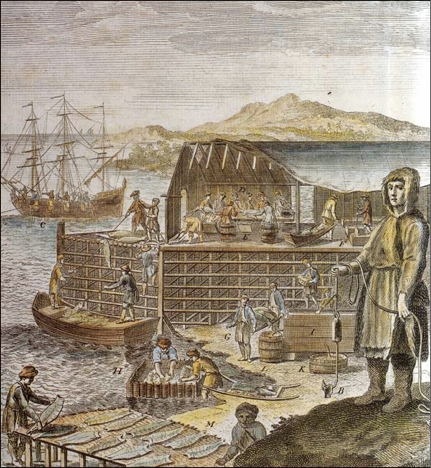

Renews and Trepassey are blessed with the finest harbours in the southeast Avalon. Their proximity to the Grand Banks and relatively flat foreshores provided ideal sites for the laying out, salting, and drying of cod on wooden platforms called “flakes”.

http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/politics/images/migratory-fishing-stage.jpg

http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/politics/images/migratory-fishing-stage.jpg

There are almost no records of their interactions with the Indigenous population, the Beothuk, who lived primarily inland. The Beothuk evidently observed the strangers’ comings and goings, and salvaged iron nails, fish hooks and other items left behind by the fishers. By the 19th century, European settlers engaged with the Mi'kmaq, Algonkians who settled along the south coast of the island.

While some fishermen may have overwintered in the 16th century, their usual practice was to store smaller boats and fishing equipment onshore and sail back to Europe in late fall with their cargo. The first attempts at permanent settlement in the area are attributed to the Welshman Sir William Vaughan.

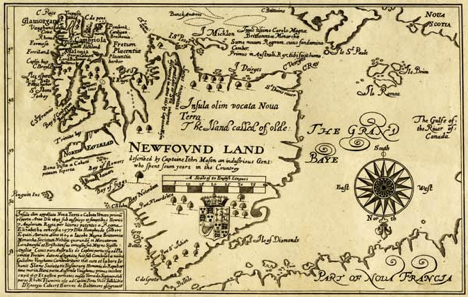

After a failed settlement at Aquaforte, Vaughan moved his colony to Renews in 1619, and in the early 1620s to Trepassey. His vision was to provide better economic opportunities for poor Welsh sheep farmers who he hoped would graze sheep on the barrens and engage in the salt-cod trade. The Renews settlement appears to have been poorly organized and failed. By the 1630s the Trepassey settlement also failed. The reasons are not entirely evident from the meagre historical record. Both Renews and Trepassey were permanently settled later in the 17th century.

http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/images/mason-map-newfoundland-1617.jpg

http://www.heritage.nf.ca/articles/exploration/images/mason-map-newfoundland-1617.jpg

Renews and Trepassey are steeped in history. Renews was visited by Jacques Cartier in 1535. In 1620 the Mayflower briefly stopped in Renews to provision before its final landing at Plymouth Rock. Samuel de Champlain visited Trepassey in 1620 on one of his many trans-Atlantic crossings.

For more information on these settlements see: A History of Trepassey and A History of Renews.

Other settlements in the southeast Avalon were founded much later. Cappahayden and Chance Cove (and later abandoned) were settled by residents from Renews. On the southern shore, Long Beach, Portugal Cove South, Biscay Bay and St. Shott’s, were settled by residents from Trepassey. The St. Vincent’s area was seasonally occupied by Basques in the 16th century but permanent settlement did not take place until the late 18th century. This was probably due to difficultly of founding landing piers due direct exposure to the ocean. The safe anchorage in Holyrood Pond has always been difficult to access due to the shifting sands at the entrance occasionally completely blocking access.

Human Impacts on the Landscape

Despite such a long history of settlement, human impacts on the natural landscape have been surprisingly minimal. The Indigenous people used the resources of land and sea, but left few structures. Europeans initially cleared land near harbour landings of spruce and fir to provide flakes on which to dry salted cod. Vaughan’s settlers built houses, maintained cottage gardens and created meadows for their livestock, primarily horses for tillage and hauling firewood, and for grazing sheep, horses and cows. It is possible that some areas of the hyper-oceanic barrens were once covered with trees. If human disturbance was a factor in their removal it was probably through deliberate use of fire.

Local sheep grazing in a meadow in Trepassey harbour

Local sheep grazing in a meadow in Trepassey harbour

In older communities such as Renews and Trepassey one can still see rock fences used to delineate boundaries and to contain farm animals. It is highly likely that cows and horses and in particular sheep, grazed on grasses on upland portions of the barrens. It is also likely that the Newfoundland Wolf (now extinct – see https://www.therooms.ca/the-newfoundland-wolf-0), which fed primarily on caribou, was a predator to be reckoned with. The sheep themselves created well defined tracks along the coast that can still be followed today. The Newfoundland Local sheep, while not a recognized breed, are a distinct landrace, and are seen sometimes along the coast, particularly in Trepassey and St. Vincent’s. Coyotes have replaced the wolf as the local wild predator.

From the 17th century on, traditional local practice was to fish in the spring, summer and fall and in winter cut spruce and fir for firewood and to replenish flakes. Residents supplemented their fish diet with meat from sheep and cows, and also hunted Caribou, Snowshoe Hare, Willow Ptarmigan and Ruffed Grouse. In the summer residents hunted seabirds and collected their eggs from the main local colonies at The Rookery and Freshwater Cove on the Cape Race Road, and at Cape Pine.

After the fishing season local seabirds leave the area to be replaced by huge numbers of wintering Common Eiders, which provided an important source of winter food. There is a plaque just west of Cape Pine near Arnold’s Cove dedicated to three lost bird-hunters.

Life has never easy for people living in this area and many outports of Newfoundland. The harsh conditions and isolation have forged a long history of genuine sharing in times of need. Just about everywhere you go in Newfoundland urban visitors experience a kind and welcoming people grounded in a sense of place so often difficult to find in the big city.

A raft of Common Eiders is a common sight in winter along the south coast. Photo Clifford Doran

A raft of Common Eiders is a common sight in winter along the south coast. Photo Clifford Doran